Cross-linguistic studies involve a lot of data collection. If we want to make the most progress towards understanding something, it makes sense that we should make our work usable for people besides ourselves. We might be able to get some additional help!

When I started the concord typology project as a researcher, I knew I wanted to keep track of my data in such a way that other researchers could easily build on the work I had done. I also wanted to make sure that anybody who wanted to retrace my steps would be able to without having to build the study from scratch. After writing the proceedings paper based on the initial results, I uploaded the data (with the paper) to OU/OSU/OCU’s SHAREOK archive. Here’s what’s in there:

- Main article: the proceedings paper (geared towards academic audiences)

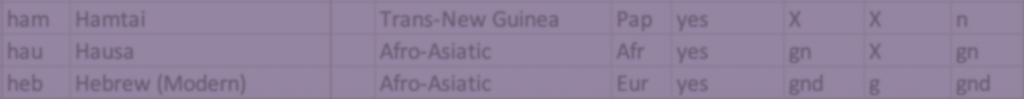

- Research data (spreadsheet): all the coding and classification I did based on the data that I collected; easy to digest reasonably quickly

- Research data (read me): an explanation of the contents of the archive

- Research data (examples + examples appendix): the actual linguistics examples that the spreadsheet is based on; sort of like research notes and thus not as easy to digest

I spent some time cleaning up the data to prepare it for eyes other than my own, but it’s hard to perfect it on the first pass. I called it good enough and then got back to work collecting more data.

One year later, someone finds and uses the data!

About a year after I published my data in the archive, I got an email from Kyle Mahowald, an assistant professor of linguistics (at UC Santa Barbara) who is interested in computational modeling of cross-linguistic studies (like mine). He stumbled upon my data and decided to start building a model based on the data that could account for issues of genetic and geographic proximity. This was, of course, very exciting: somebody was building on the work that I started! I spent a good deal of time getting the data ready for the archive, so seeing that somebody found it and used it made all that effort worthwhile.

This brings me to my next point: when you think about making your data usable, consider the user carefully, and make sure the data is as usable as possible. In the version in the SHAREOK archive, I made a choice that negatively affected usability. When Kyle initially wrote the model, it was making a few predictions that were strikingly different from my results. The issue arose from the coding schema I used for for the spreadsheets. In brief: there was an overlap in some of the labels I had used, and so the script was treating some distinct labels as though they were the same. The bug was an easy fix, but we only noticed it because Kyle and I started collaborating and discussing the model he developed. It got me thinking about how I could make my data not only available, but (even more) useable.

Iterating towards better usability

After my initial conversations with Kyle, I put some work in to improve the usability of my data. I wanted something that achieved a balance between these three things:

- Easy to read (for humans)

- Easy to process (for computers)

- Easy to update (for me)

For this, I settled on storing the coding for each language as a JSON file (as I mentioned in this post). I find JSON files relatively easy to read—especially if you save them with some formatting for readability—and they can be easily converted to other formats. I wrote a few scripts to convert the existing overlapping labels into a system without overlap. And to add new data, all I have to do is add a JSON file for the language I just documented (which I’ve already written a script for).

I now store and update the data on OSF, a free and open platform for sharing research. This means anybody (even you, dear reader) can download the current state of the study this very moment! If you don’t have experience working with JSON files yourself, don’t worry: I have a script on my github that processes the important data from all the JSON files and saves it as a single CSV. So, even if you haven’t used anything besides Excel/Sheets, you can still look at the data!

Keep your data user-friendly!

To sum up, the big lesson here is to keep your data user-friendly. If you want whoever uses your data—be they a research colleague, a coworker, or a client—to be able to build on the work you’ve put in, think about how they might use the data and try to make that as easy as possible.