Before you read too far, let me issue this disclaimer: when I say case in this blogpost, I am never talking about syntactic Case with a capital C.

If you ask anybody who works on generative nominal morphosyntax where case is, my guess is that most of them will bring up KP, a head that (most of the time) is assumed to take a DP complement. The earliest citation I’m aware of for KP is Lamontagne & Travis (1987) (see also Travis & Lamontagne, 1992), but since as early as 2005, people have been using KP without citation. I think many/most NP generative syntax folks would not disagree with a statement like, “KP is the location of case features,” but there are in fact very few works that carefully explore the connection between K and case morphemes.

Case = K: Case particles

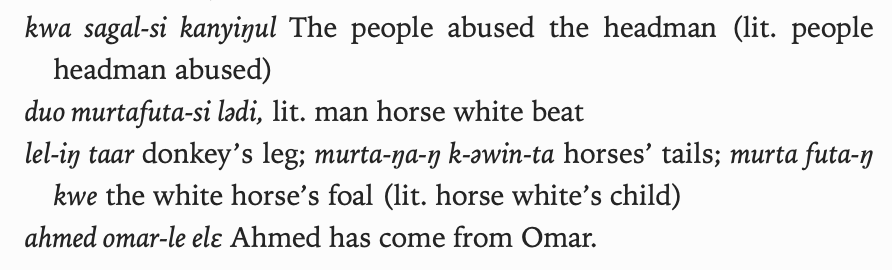

I can’t get too in the weeds with this (b/c blog), but here’s one example where the connection between case and K is brought up. At the beginning of their paper which is mostly about nominal licensing (but does use KP), Bittner and Hale (1996:4) suggest that the order of case particles and nominal phrases tracks that of verb and object.

But they do not cite or report on the results of a typological study. And Dryer’s sample of case affixes does not include case particles. However, the border between adpositions and case is fuzzy, and since adpositions also closely track VO order, I expect it’s true that case particles do likewise (to the extent that a border between case particles and adpositions can be established).

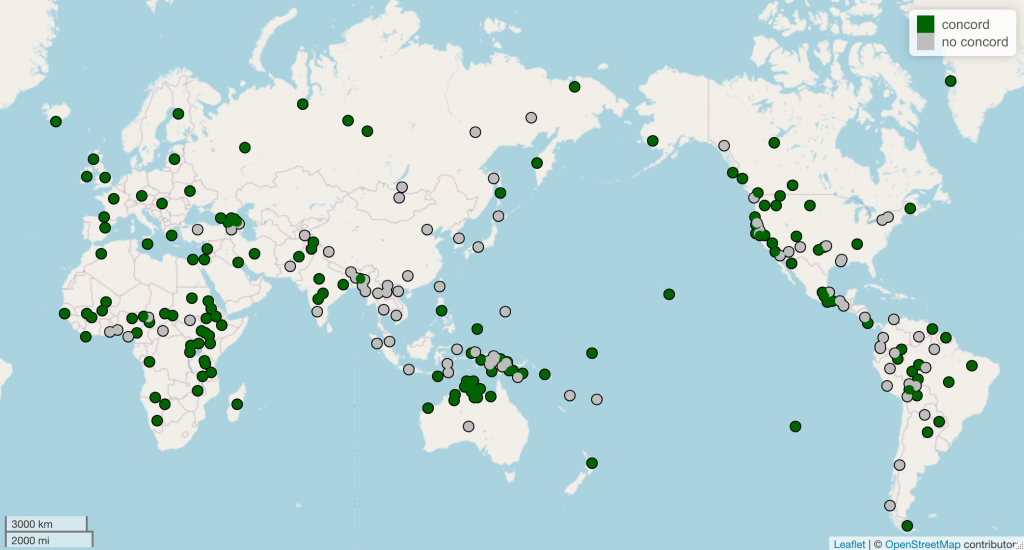

Case ≠ K: Case concord

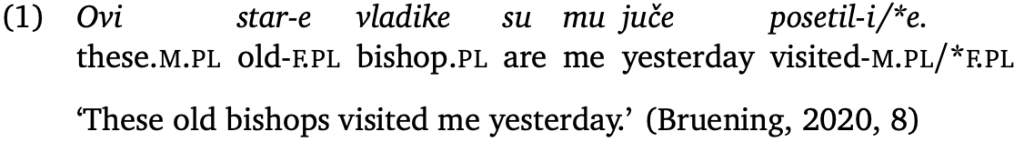

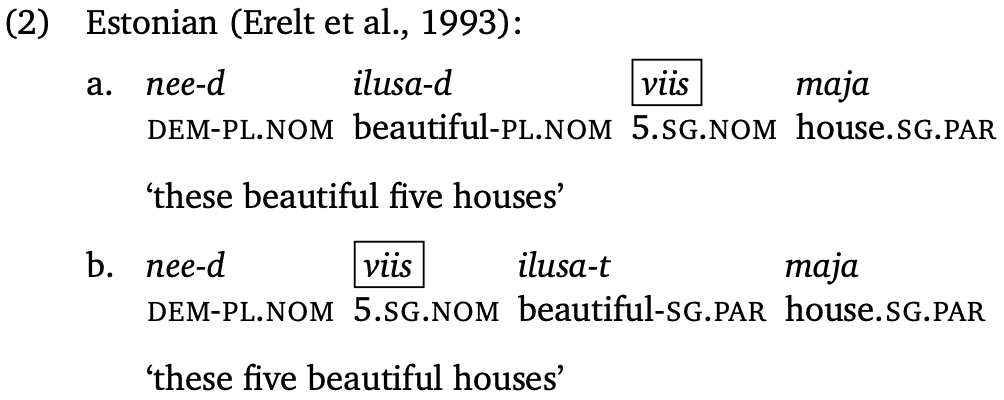

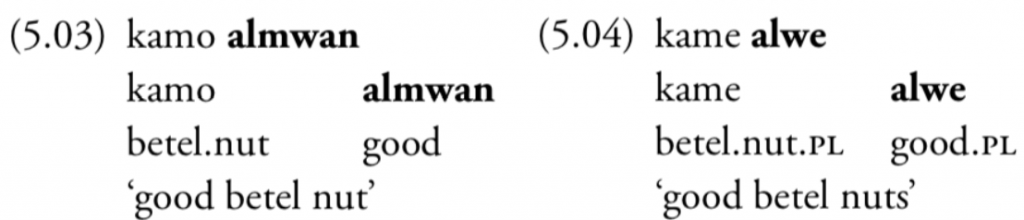

The mapping between case and K is clearest in these case particle languages, because there is one case morpheme and one syntactic locus (and 1, as they say, = 1). There are languages with case multiple times per NP (languages with case concord), and here it is not clear what the connection is between K and case. Take, for example, Estonian:

In my NLLT paper (and in my other work on case concord), I do treat case as originating on K in some sense, but I do not specify how the K head itself is realized. I believe the same is true for Ingason (2016), who discusses case concord in Icelandic (hmm, where have I heard of that before?). When people would ask me about this when I was in grad school, I would provide a joke answer of, “Oh, I like to pretend the K head explodes and rains down its pieces on the heads below,” but I did not have a real answer. The only plausible answer (that I don’t anticipate working out any time soon) is that K is realized as case on the noun.

There are some other approaches, too, like treating case as a feature assigned to a phrase rather than originating on a head (Baker and Kramer, 2014:148) or inserted as postsyntactic morphemes (eg, Embick and Noyer, 2001).

Case ≟ K: other case suffixes

The missing piece of this investigation imo are languages with case suffixes but no case concord (or at least, no robust case concord). I have wondered: in a language with no case concord but a case suffix on N, how does case end up on N? Sometimes, nothing special needs to be said. In an N-final language like Turkish, case could be a suffix in K and just end up landing on N because they happen to be adjacent. So I went looking in my concord sample for languages that were [-Nfinal, +case, -case concord] to see where the case morpheme ended up.

A number of these languages are coded by Dryer as having postpositional clitics—the case marker ends up on whatever word is last in the NP (or perhaps there are some restrictions, but the idea is that case can attach to a variety of bases). There were also a number of languages reported as having case suffixes, but when I looked more closely, I found that in fact many of these languages might actually have postpositional clitics instead. I only say “many” because I don’t have clear data for some of them, but importantly: I don’t have any examples showing a bound case formative on a non-final N in a language without case concord. (!!) What! Here are a couple examples to show what I mean

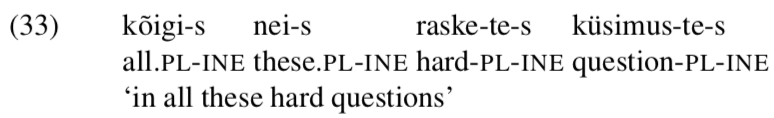

Yuchi (ISO yuc; isolate, North America)

Yuchi is coded as having case suffixes, but in Mary Linn’s grammar of the language, I found a couple examples where the case morpheme was not on the noun, but on its modifier. This would be evidence for labeling Yuchi case as a postpositional clitic. (Dryer’s data come from a different source for Yuchi, so I can’t say for sure what the discrepancy is.)

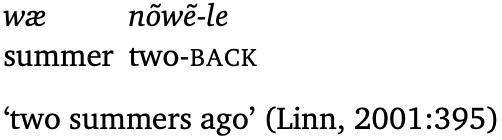

Fur (ISO fvr; Fur (controversially Nilo-Saharan), CAF/Chad/Sudan)

Fur is also characterized as having case suffixes, but in examples from Tucker & Bryan (1966), the case marker attaches after postnominal adjectives.

Again, if these examples are representative (and, of course, assuming it’s reasonable to treat adjectives as different from nouns in Fur), then these are more like postpositional clitics, too.

Hang on, I’ve lost the thread.

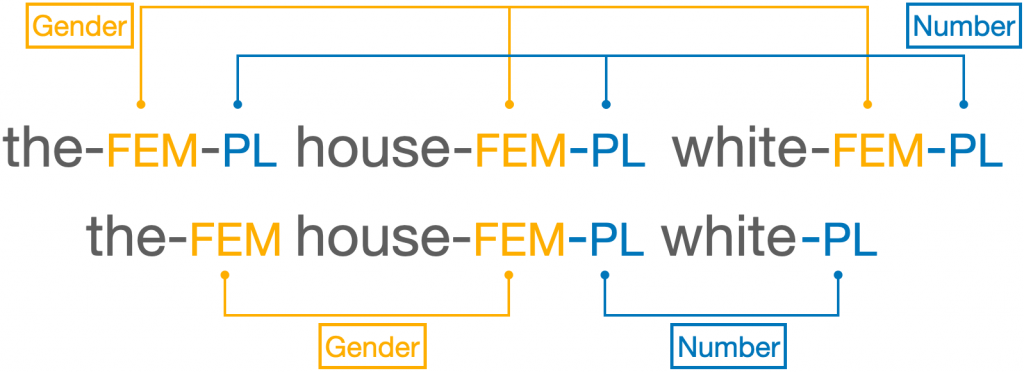

Blogs are hard. The point is this: Nobody has (to my knowledge) a worked out demonstration of what needs to be said to maintain that case morphemes are connected to a high head in nominal phrases (“call it K, if you like”). There should be one— or there should be something talking about why that can’t work. I say that because there is such interesting work on gender and number in this domain. Why not case? I guess it could be because case has a more indirect relationship to the noun and thus has less noun-related idiosyncrasy, by and large. Or it could be that in many languages, cases are just tiny and/or dependent adpositions, and there’s not a lot of morphology to adpositions generally.

If I wanted to take the time to re-write this (not really how blog posts work), it might look like this:

- Are case formatives realizations of K?

- Easiest stuff: case particles

- Pretty easy stuff: peripheral case affixes/clitics in N-final languages

- Pretty hard stuff: Case concord

- Pretty does it exist stuff: that puppy-ACC fuzzy is a pattern we don’t expect and importantly, we don’t see it (very often)

Somebody get into case formatives! End of blog post.